The Full Story

Chilling discovery of the Blythe Star shipwreck 50 years after its shock disappearance, reminds us what has been achieved in the years since for seafarers’ safety

The shock discovery of the Blythe Star, almost 50 years since its mysterious sinking, is a chilling and poignant reminder of one of the most significant moments in Australian seafaring history; one that led to significant and lasting reforms to shipboard safety and improved search and rescue procedures which have protected the lives of many thousands of seafarers since.

The 44-metre motor vessel (MV) Blythe Star was a coastal freighter that disappeared off Tasmania nearly 50 years ago. The vessel was travelling from Hobart to King Island when, on 13 October 1973, it suddenly capsized and sank off the southwest coast of Tasmania. All 10 crew members were able to escape the sinking vessel into an inflatable life raft.

Tragically, three crew members died before the survivors were able to find help and be rescued 12 days later on 24 October 1973.

The location of the MV Blythe Star was confirmed by the CSIRO’s Marine National Facility, using its research vessel, the RV Investigator, on 12 April 2023 during a 38‑day research voyage to study a submarine (underwater) landslide off the west coast of Tasmania. This voyage included a piggyback project to investigate an unidentified shipwreck which had been pinpointed by fishing vessels and previous seafloor surveys in the region.

Listen to the ABC’s podcast, From the Dead, about the sinking of the Blythe Star

The CSIRO Investigation

Search for it.

The location of the wreck of the MV Blythe Star was confirmed by RV Investigator on 12 April 2023 during a research voyage off the west coast of Tasmania. The primary purpose of this voyage, led by the University of Tasmania, was to study a massive underwater landslide on the continental shelf in the region, with the search for and identification. The voyage included a ‘piggyback’ project to investigate an unidentified shipwreck in the region.

Map it.

Systematic mapping of the unidentified shipwreck using multibeam echosounders was performed, then a visual inspection using two underwater camera systems. The mapping data and video imagery collected by the CSIRO was able to confirm that the shipwreck was the MV Blythe Star. Ocean currents, cloudy conditions and marine life all presented challenges during this process.

Document it.

The mapping was used to plan the deployment of the underwater cameras from RV Investigator. The team onboard would carefully manoeuvre the cameras from the stern (back) to the bow (front) of the wreck, searching for key features to confirm its identity. They would compare the vision from below to the many historical photos of the MV Blythe Star that plastered the walls and desks in the Operations Room on RV Investigator.

Mick Doleman, survivor

“I never knew anyone was even looking for it. The last time I saw it, it was sinking stern first in southern Tasmania.”

The sinking of the Blythe Star

At 8am on Thursday 11 October 1973, waterside workers arrived at Hobart’s Prince of Wales Bay to begin loading pallets aboard the Blythe Star. The next day, by 6pm, the loading of the ship was finished and the crew were making preparations to leave.

At 6:30pm the coastal freighter departed Hobart, bound for for King Island with her cargo of fertiliser and beer.

Fourteen hours later, the ship sank almost completely without warning.

The weather forecast had been ideal for a two-day voyage of almost 350 nautical miles to the island northwest of Tasmania, but why within hours of their departure were the crew of ten fighting for their lives and about to embark on a tragic, twelve day ordeal that would leave three of their number dead and rewrite the rules for Australian maritime safety?

On charter to the Tasmanian Transport Commission from the Bass Strait Shipping Company, Blythe Star was a post-war freighter weighing 321 tons gross and propelled by a 650-horsepower diesel motor that gave a steady 9.5 knots. Its voyage to King Island was to be its 38th for the Transport Commission, and nobody had any inkling it would be the ship’s last.

On this fateful voyage, the ship’s master, Captain George Cruickshank, had decided to travel from Hobart to King Island via Tasmania’s west coast, as the west-about route was four-and-a-half hours shorter than via the east coast. Before casting off he checked his load line to satisfy himself he wasn’t overloaded, then took his ship out into the River Derwent.

But as the ship reached South West Cape of Tasmania, something went wrong.

'At about 8 or 8.30 am, the ship took a starboard list... It corrected itself, then it took a further list, which was a death roll. It just went over,' crew member Mick Doleman told the ABC, recalling that he and Seaman Malcolm McCarroll were thrown out of their bunks by the ship's movement.

“I looked at my porthole and all I could see was salt water. I stood and watched and I was waiting to see a bit of sky, waiting to see her right herself, but it was pretty obvious that she wasn't going to.”

Malcolm McCarroll, interviewed on ABC Radio in 1973

The bosun, Stan Leary, had prepared and launched the inflatable lifeboat, and the crew clambered in as the Blythe Star rose up and then sank out of sight.

Sitting inside the lifeboat, which mercifully was one equipped with a canopy, they took stock of their situation. It became clear that the Captain had not been on the bridge when the ship went down and so he could not have got a distress signal away.

The emergency radio had also been left on board and was now on the bottom of the ocean floor with their ship.

Still, the men had emergency supplies with them: tinned water, dry biscuits, some flares, two oars, and a bailer to try and keep themselves dry and the lifeboat afloat.

The crew assumed that, in time, they'd be spotted and taken up to the lighthouse at Maatsuyker Island, most likely by that evening.

However, that was not to be. Due to regulatory gaps and poor safety management at the time, the alert was not raised until two days after the ship went down when it failed to arrive at King Island. There was further confusion too because ships leaving Hobart heading north have a choice of which side of Tasmania they sail around, and the ship's planned course had not been registered with or communicated to the authorities. Those searching for the Blythe Star couldn't be sure on which side of the island the ship had disappeared, how far along its journey it had travelled or where to begin their search.

The ordeal and the rescue

For eight days the lifeboat drifted around the south of Tasmania at the mercy of the winds and strong ocean currents.

Two or three crew members had been in bed when the capsize occurred and were dressed only in underpants and a T-shirt when the ship went down. They were at constant risk of hypothermia.

The captain gave his jacket to 18-year-old seaman Mick Doleman, who’d been thrown from his bunk, but of course no one of them was properly dressed for an eight day ordeal on the Southern Ocean, and every crew member aboard the lifeboat suffered mightily from the extreme cold.

Throughout the first two days, the lifeboat the raft drifted around the Pedra Branca archipelago – which they crew would have known was site of many shipwrecks. They paddled ferociously to keep the inflatable lifeboat, their only lifeline, clear of the jagged rocks.

The fourth day was when the first of three tragedies struck. Soon after morning broke, the crew came to the harrowing realisation that John Sloan, the second engineer, had passed away during the night. Separated from an on-board supply of thyroid medication to manage a chronic health condition, he succumbed to the cold and wet conditions, however, remaining certain that surely a rescue effort was underway and they could only be a matter of hours from being winched or towed to safety, the men kept the body of their shipmate aboard.

All that day, the raft rolled and pitched in heaving swell. The men paddled in shifts, trying to stay within sight of the coast and steer towards civilisation along the sparsely populated, remote Tasmanian coastline.

By nightfall, they grappled with the grim reality that the rescue had not come. The body of John Sloan was given a sea burial—it was pushed over the side of the raft into the freezing waters of the South Pacific Ocean.

Sloan's singlet and socks ended up with Doleman. 'I thank John,' he told the ABC in a retrospective, published in 2015. “I knew damn well that he'd be more than happy about that—for his fellow shipmates to use a bit of his clothing to keep warm,” he said.

Still adrift and no nearer to shore on their fifth day of the ordeal, the nine remaining crew members paddled and bailed out the circular, inflatable lifeboat, rationing fresh tinned water as best they could.

“The weather was absolutely appalling,” recalled Doleman in 2015.

“At times the raft would concertina into itself—you'd have people on the left and right hand sides of the raft smashing into each other.

“We'd have enormous waves bursting through the canopy, so we had to get the water out. We were wet the whole time.

“But then we had weather that just blew us further and further south. Had we kept going we would've ended up in Heard Island or Antarctica.

“It was extremely cold, and no sign of any land. Not even any birds, and if you can't see any birds at sea you're a fair way from land.

“Thankfully, the current and the prevailing weather changed and brought us back up to Schouten Island, which is on the eastern side of Tasmania.”

Reflecting on the latter days of the ordeal, Doleman says that by morning on the ninth day the crew’s morale was absolutely smashed and they were each completely exhausted, bordering on unable to persevere.

But at daybreak on that ninth day, Doleman realised that the crew was closing in on a bay.

Early on the morning of Sunday 21 October, after traversing 400 kilometres of the Southern Ocean, the raft had drifted into Deep Glen Bay, a tiny rocky bay on Tasmania’s east coast, about 75 kilometres southeast of Hobart.

“I just made a decision: I'm not going back out to sea. I jumped out of the raft and thankfully the water just come up to my waist,” he said.

“Funny part was, after we got ashore we all jumped out thinking we'll be able to run up the beach and just lay down and congratulate each other and everything,” Malcolm McCarroll told the ABC in 1973.

“But you can't walk. It's as if you've been drinking all day, as if you're as full as a boot,” McCarroll added at the time.

Stumbling ashore, the men quenched their burning thirsts from a little creek flowing into the rocky cove.

A few hours after making landfall, Chief Engineer John Eagles crawled down the shore to the raft, laid down beside it and passed away. Early the next morning, First Officer Ken Jones succumbed to the same fate. The hypothermia and exhaustion had overwhelmed them.

These two men’s deaths had a crushing effect on the remaining crew, who by now would have been in a panic that despite reaching dry land they were still no closer to being rescued.

Surrounding the cove were 200 metre high cliffs, near vertical at every point, and the bush was thick and dense. Standing at the bottom of them, you can’t see their tops.

Dunalley Post Office, where the trio were taken by truck to call for help

A day later, after a wet and cold night spent in a hollow log beneath ferns and leaves for shelter, the three men smashed their way through dense bush to find themselves on a remote ridgeline, but in sight of a logging track.

“Lo and behold, we walked out of the bush and here's a dirt track,” Doleman explained to the ABC.

“Seeing a dirt track—you have no idea just how enthralling a dirt road is to someone who had been in the circumstances we were in,” he said.

Then, in the distance, they heard the grinding of gears.

Running to the truck, Doleman yelled, “Don't go! Don't go! We're from the Blythe Star!”

The driver of the truck, understandably, responded in disbelief: “You're dead!”

“No,” said Doleman. “We're not.”

Legacy of the Blythe Star

Inevitably, after what amounted to a botched search and rescue effort, an Inquiry was held into the loss of the Blythe Star and the tragic, preventable deaths of the three crew members.

While the cause of the capsizing or foundering of the ship remained a matter of some debate, what could not be disputed was that a ship’s lifeboat, properly prepared and launched, with ten crew aboard, should not have been adrift for nine days without detection.

The Federal Government’s response to the tragedy included an amendment to the Navigation Act to requires ships of 300 tons or more to lodge a sailing plan and give daily position reports. For the Blythe Star, these measures would have raised the alarm within hours of the foundering, and would have narrowed the search area to a small section of coastline rather than a stretch of coastline spanning the length and breadth of the Tasmanian coast.

The AusRep system that ensures mariners regularly report their routes to authorities and requirements for all life rafts to be fitted with radio beacons was introduced to prevent a similar traged. As technology has advanced, this now takes the form of EPIRBs that are required even by private pleasurecraft that travel more than two nautical miles offshore.

Deep Glen Bay, South East Tasmania

Despite several attempts, the crew could not find a way out that first afternoon, nor the next day.

“Someone said, ‘Well, we're never going to get out of this canyon. Why don't we get back in the raft and paddle around?’” Doleman recalled to the ABC in 2015.

Doleman wouldn’t countenance it.

“There was no way in the world I was getting back in that raft. And I wasn't going to let anybody else get back in it,” he explained. “I went and got a knife and I cut the raft up and I made clothes out of it. I made a lap-lap and a jacket type thing to keep the wind out.”

The remains of the raft are now kept at the Maritime Museum of Tasmania.

So with boots and ponchos made of the slashed raft, on the morning of Tuesday 23 October the three youngest members – Mick Doleman, Mal McCarroll and the ship’s cook Alf Simpson – left the camp knowing that if they didn’t find help that they would surely die on the beach alongside their crewmates.

“I'd rather die trying that just dying here on that beach. We'd already lost two. I figured it wouldn't be much longer until there'd be others,' Doleman said.

Unbeknownst to the crew, the main sea and air search had been called off by this stage – with the assumption that all had been lost aboard the vanished ship.

Memorial plaque at Deep Glen Bay

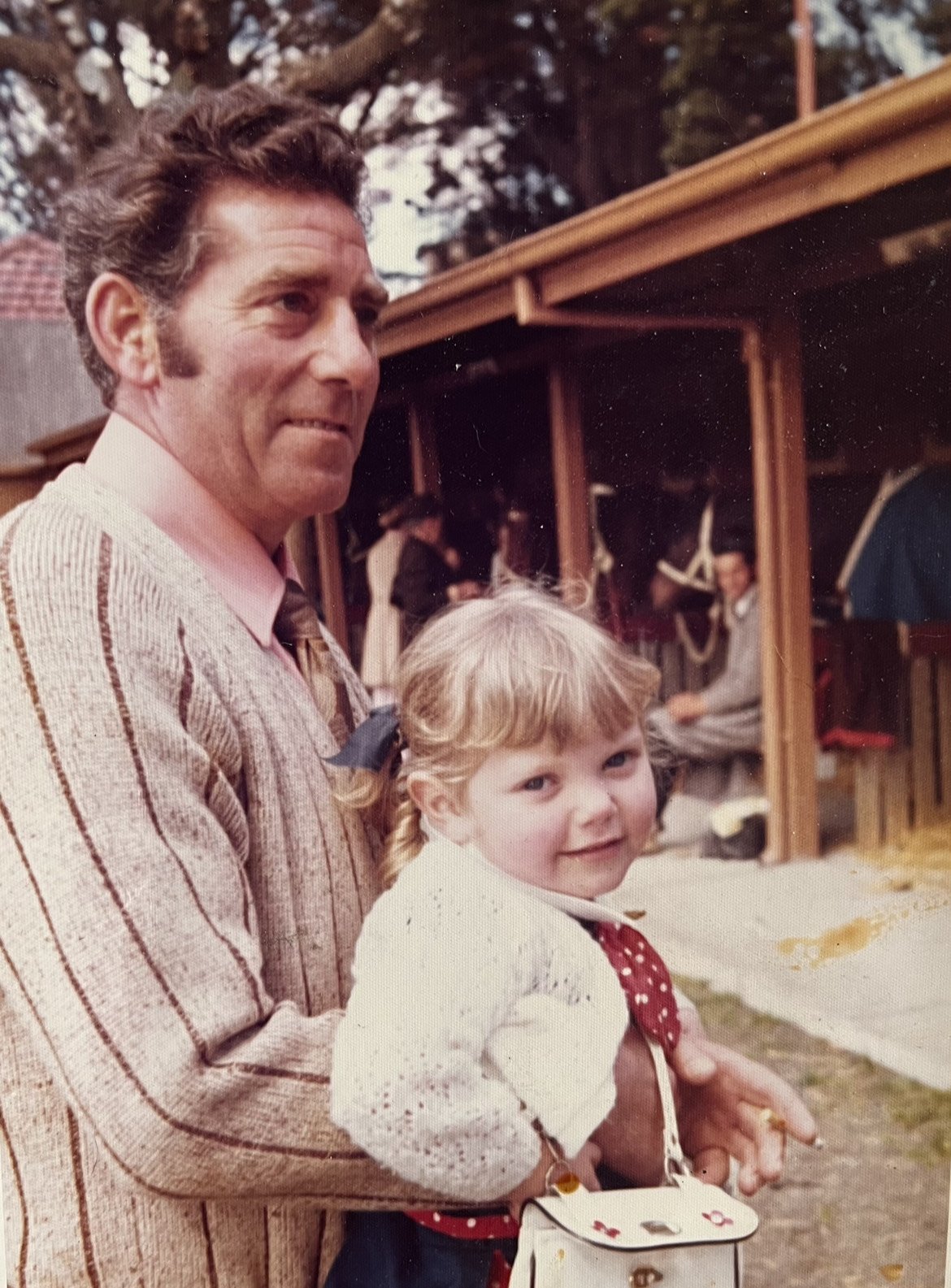

Blythe Star Chief Officer Ken Jones with daughter Susan McKenna